by Cristina Neri | March 11, 2009

I hate to be the bearer of bad news, but overall 2008

was somewha of a lackluster year for new Region 1 DVD

releases of ’60s and ’70s era films when compared to

the previous two years (See: 2006&2007).

Some of my favorite DVD companies such as BCI Eclipse

and most recently New Yorker Films have folded.

Boutique DVD companies are releasing fewer products

and what is being released is often of questionable

quality. With the failing economy and the rise in

popularity of Blu-ray discs, it seems like the number

of new worthwhile DVD releases might continue to drop

dramatically in 2009.

Many companies such as Blue Underground and Criterion

are choosing to re-release films that have already

been available on DVD, while big studios like Warner

Brothers and Paramount seem to be focusing a lot of

their energy on re-releasing titles on Blu-ray instead

of releasing old films from their vaults.

Even with this disappointing turn of events, fans of

’60s and ’70s cinema were still offered some great DVD

box sets from companies like Lions Gate as well as

Criterion. Sony Pictures has also released an interesting

batch of DVDs under their new "Martini Movies" label.

And with curiosity about Japanese pink films on the

rise, companies like Mondo Macabro and Media Blasters

took full advantage of this and released some unexpected

gems last year. 2008 was also a great year for British

horror fans. Besides multiple Hammer DVD releases

including the Icons of Horror: Hammer Films Collection

and the Icons of Adventure Film Collection, there were

also some great Amicus films released such as Freddie

Francis’ The Skull and The Deadly Bees. In previous

years I’ve shared a list of my Top 30 Favorite DVD

releases, but this year I’m narrowing my list down to

my favorite Top 20 releases.

This is mainly due to my disappointment with last

year’s DVD offerings and I wanted to focus on a limited

selection of new releases that I really enjoyed.

As always, my list only features films that were originally

released between 1960 and 1979 on Region 1 DVD. I tried

not to include any DVD re-releases on my list or TV shows,

but there were plenty to choose from. My selections are

listed in alphabetical order and I’ll be posting them

in two parts in the coming week.

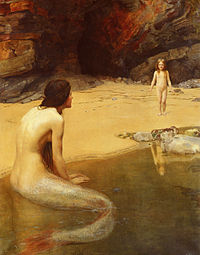

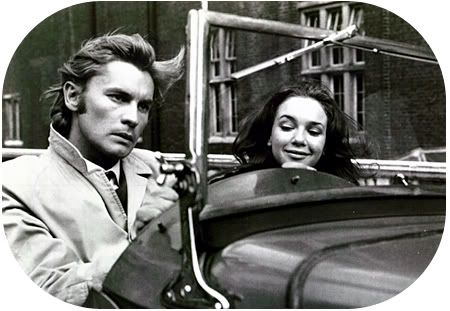

Alain Delon and Romy Schneider in La Piscine (1969)

1.Alain Delon - Five Film Collection (Lions Gate)

Anytime an Alain Delon film finds it’s way onto DVD

for the first time there’s a celebration in my home!

The Lions Gate Alain Delon DVD boxset was a real treat

and offered viewers the opportunity to see five films

starring my favorite French actor. I thought the best

films in the collection were easily La Piscine aka

The Swimming Pool (1969) and Diaboliquement vôtre

aka Diabolically Yours (1967), which I reviewed back

in 2007. But The Widow Couderc and Notre Histoire

also make for some worthwhile viewing. Le Gitan aka

The Gypsy (1975) is a bit like sitting through

Zorro II, but it’s missing the catchy theme song.

I actually enjoy Delon’s original Zorro (1975) film,

but Le Gitan left me a little cold. For more

information about this DVD release please see my

previous comments about it here.

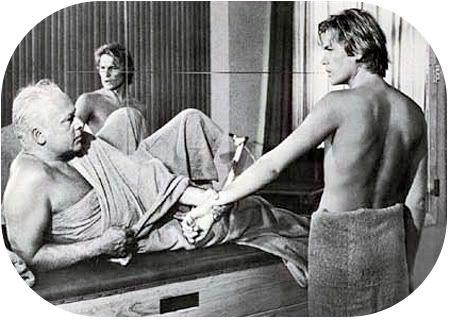

Christopher Walken, Stan Gottlieb and Sean Connery in

The Anderson Tapes (1971)

2. The Anderson Tapes (Sony Pictures)

The Anderson Tapes (1971) is one of the hidden gems that

can be found in the recent batch of “Martini Movies”

released by Sony Pictures. This ’70s caper film was

directed by Sidney Lumet when he was at the top of his

game and it’s based on a novel written by Lawrence Sanders.

The movie features a great cast that includes Sean Connery,

Dyan Cannon, Martin Balsam, Alan King and a very young and

incredibly cute Christopher Walken in his first major film

role. The premise of the film involves a group of con men

that Anderson (Sean Connery) brings together in order to

pull off a major heist at an upper-class apartment building

in New York. Unfortunately for Anderson everyone he contacts

is under surveillance for different reasons, so every move

he makes is being carefully monitored. Sidney Lumet does an

impressive job of filming the events as they unfold through

the use of surveillance cameras and sound. And I really

liked the adult way that Connery’s relationship with Dyan

Cannon was handled. The film was released a year before

the Watergate scandal made headlines and three years before

Francis Ford Coppala’s seminal film The Conversation,

which tackled similar themes. I was surprised by how much

The Anderson Tapes had obviously influenced Coppola’s later

films and I’m not just referring to The Conversation.

Clearly writer Lawrence Sanders and director Sidney Lumet

were well aware of the way surveillance was starting to

play a role in modern society and the film does a terrific

job of exploring the way it invades the life of one

unsuspecting man. Quincy Jones created the film’s soundtrack

and I think is one of the composers most experimental and

unusual efforts. Jones used electronic sounds and noise to

convey various emotions and ideas in the film and it works

really well with the way Lumet handles the material.

The film is presented in widescreen and the print looks

terrific. Unfortunately there aren’t a lot of extras on the

DVD besides the original trailer and the Martini Movie

features which come with every one of their releases. Assault! Jack the Ripper (1976)

3. Assault! Jack the Ripper (Mondo Macabro)

This is not an easy film to recommend and many will

undoubtedly be shocked by the film’s subject matter.

Some hardened horror fans will even shy away from the

graphic nature of the film, but Assault! Jack the Ripper

(1976) is easily one of the most transgressive and

fascinating violent pink movies I’ve seen and in turn,

one of my favorite DVD releases of last year.

Assault! Jack the Ripper was directed by Yasuharu

Hasebe who has made some of my favorite Japanese films

including Black Tight Killers (1966), Bloody Territories

(1969), Female Prisoner Scorpion: #701’s Grudge Song

(1973) and the Stray Cat Rock films. The movie centers

around the violent and erotic adventures of young working

couple who accidentally discover that they get sexual

satisfaction from torturing and murdering other women.

The film used true crimes such as the notorious Chicago

nurse murders committed by Richard Speck for inspiration.

It’s propelled by an incredible Euro-flavored soundtrack

and some breathtaking cinematography. Assault! Jack

the Ripper is not light viewing and audiences should be

prepared to watch the DVD extras that come with the film

in order to get a deeper understanding of the movie’s

subversive themes, but it’s well worth the effort for

adventurous viewers. The DVD extras include an insightful

interview with author Jasper Sharp who wrote Behind the

Pink Curtain: The Complete History of Japanese Sex Cinema,

extensive notes about the film and a great documentary

called The Erotic Empire which discusses Nikkatsu Studios

“Romantic Pornographic” aka Roman Porno films.

Blue Eyes of the Broken Doll (1973)

4.Blue Eyes of the Broken Doll (Special Edition)(BCI / Eclipse)

A lot of Paul Naschy films found their way onto DVD

last year, but Carlos Aured’s Blue Eyes of the Broken

Doll (1973) was my favorite of the bunch. In this

Spanish giallo Paul Naschy plays a deeply troubled

ex-con who gets hired as a caretaker for a lavish estate

owned by three beautiful sisters who seem to all vie for

Naschy’s affections. After Naschy takes the job, a serial

killer begins terrorizing the countryside and removing

the eyes of his blue-eyed victims. Is Naschy the

cold-blooded killer or is someone else to blame for the

horrible murders? You’ll have to watch the film to find

out! No one in Blue Eyes of the Broken Doll is

particularly likable, but I found that aspect of the film

strangely compelling. Carlos Aured does a good job with

the dream sequences in the film and Paul Naschy ’s script

features plenty of unusual twists and turns to keep

viewers entertained. Fans of European thrillers should

find the film enjoyable. The DVD comes with some great

extras including audio commentary with Paul Naschy and

director Carlos Aured.

Reiko Oshida in Delinquent Girl Boss:

Blossoming Night Dreams (1970) 5. Delinquent Girl Boss: Blossoming Night Dreams (Media Blasters)

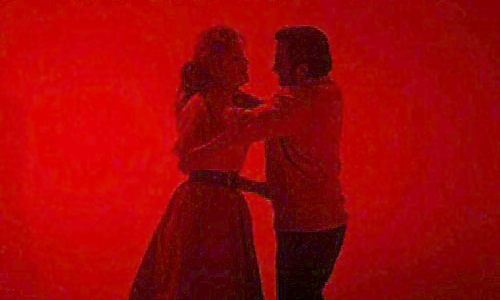

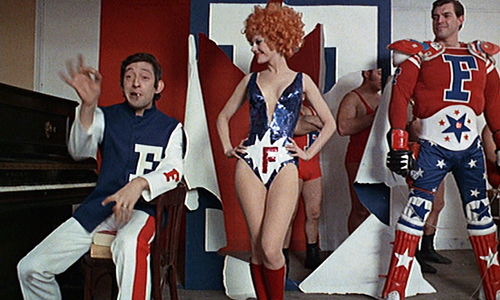

Serge Gainsbourg, Delphine Seyrig and John Abbey in Mr. Freedom (1969)

6.The Delirious Fictions of William Klein-

Eclipse Series 9(Eclipse / Criterion)

This Eclipse/Criterion DVD collection was one of the best

things the company released last year and for my money,

possibly the best DVD film collection of 2008. Previously

William Klein’s films were incredibly hard to come by and

the prints that were floating around from various sources

were often very poor. Criterion’s choice to release three

of William Klein’s films was a real surprise and a treat

for anyone like myself who enjoys avant-garde cinema from

the ’60s. Director William Klein was a fashion photographer

and an American expat living in Paris when he made these

films, which satirize the fashion industry, pervading

cultural values and American political policies.

Although some may see the films as mere products of the

times that they were made in, I think they’re still

extremely relevant today. Who Are You, Polly Maggoo?

aka Qui êtes-vous,Polly Maggoo?(1966)and Mr.Freedom(1969)

are the standout features in this three film set and I’d

be hard pressed to pick a favorite from the two. Both films

feature some incredible visuals and lots of dark humor.

The Model Couple (1977) is also well worth a look even if

it’s lacking the style and intellectual punch of the other

two films in the collection. This terrific set of films

deserves a lot more attention than I can give it now but

I briefly mentioned how excited I was about this DVD release

last year and you can find that post along with a clip from

Who Are You, Polly Maggoo?here. Unfortunately like all the

Eclipse/Criterion DVD releases this DVD collection is very

bare bones, but still well worth owning.

The Gorgon (1964) 7. Icons of Horror: Hammer Films (Sony Pictures)

I’m always happy to see any Hammer horror films finding

their way onto DVD and the 2-disc Icons of Horror collection

contained one of my long-time favorite Hammer productions,

Terence Fisher’s The Gorgon (1964) as well as Seth Holt’s

exceptional thriller Scream of Fear (1961). This four film

collection also featured Michael Carreras’s The Curse of

the Mummy’s Tomb (1964) and The Two Faces of Dr.Jekyll(1960).

I hadn’t had the opportunity to see Terence Fisher’s The Two

Faces of Dr. Jekyll before this DVD release and I was really

surprised by how well done the film was. I personally think

it’s one of the better films based on Robert Louis Stevenson’s

classic story thanks to Paul Massie’s excellent duel

performance as Dr. Jekyll/Mr. Hyde. The Curse of the Mummy’s

Tomb is definitely the weakest film in the collection,

which still means it’s better than most of the horror films

you’ll find playing at your local multiplex right now.

All the films look terrific and are presented in widescreen.

Terence Fisher and Seth Holt were two of the finest directors

that worked with Hammer studios so it’s nice to see them both

represented in this great new DVD set. Unfortunately it suffers

from a lack of extras which plagues many Hammer DVD releases,

but it’s hard to complain when you can currently purchase all

four films for a mere $16.99 at Amazon (see link above).

Oliver Reed and Carol Lynley in The Shuttered Room (1967) 8. It! The Shuttered Room (Warner Home Video)

I have so much I want to say about these two joint

British/American productions that I hate trying to

sum up my feelings in one paragraph so I may revisit

them later, but in an effort to get this list finished

up I’ll try and formulate a few quick thoughts.It!(1966)

is a highly entertaining horror movie directed by Herbert

J. Leder and it stars the talented Roddy McDowall. McDowall

plays a mentally disturbed museum curator (playing homage

to Anthony Perkins) who finds himself in all kinds of trouble

after he displays a strange statue at the museum where he’s employed.

The highly improbable plot gets more and more ridiculous as the film

unfolds, but I won’t spoil it for potential viewers. It!

is a really fun movie that has to be seen to be believed

and Roddy McDowall is terrific in it. The second film in this two

movie set is David Greene’s The Shuttered Room (1967) and it’s the

real reason you should purchase this DVD. The movie features a great

cast and two exceptional performances from the film’s star Carol

Lynley and her co-star, the late great Oliver Reed.

The script is based on a story written by August Derleth, who

was H. P. Lovecraft’s posthumous collaborator and Derleth used many

of Lovecraft’s own notes and ideas to compile his tale.

The finale result may seem a little uneven to some, but I think

The Shuttered Room is one of the few films that successfully captures

the unsettling mood found in some of Lovecraft’s best fiction.

David Greene’s direction is impressive at times, but the film is

really elevated by the experimental avant-garde score composed by

controversial British jazz musician Basil Kirchin. Kirchin composed

music for other British horror films such as The Abominable

Dr. Phibes (1971) and The Mutations (1974), but his score for

The Shuttered Room just might be his most effective.

Unfortunately this is another bare bones DVD release with no

worthwhile extras, but it’s great to see these deserving horror films

finally being made available. I’d previously only seen washed out

and cut-up prints of The Shuttered Room on television so I was

thrilled by the print quality of this new DVD from Warner.

Jean-Paul Belmondo in Le Doulos (1963) 9. Le Doulos (Criterion)

Le Doulos (1963) is one of Jean-Pierre Melville’s

earliest crime films (aka “policier”) and while it’s

missing some of the polish of the director’s later efforts,

it’s still an exceptional film featuring a truly memorable

performance from the great Jean-Paul Belmondo.

Belmondo charms his way through the film playing a

surprisingly ruthless gangster named Silien, who may or

may not be a police informant referred to as a “Le doulos”

in French slang terms. The film borrows from many classic

noir films, but Melville brings his own trademark style and

edginess to the proceedings, which gives Le Doulos lots of

modern appeal. Criterion did an exceptional job on their

release of Le Doulos and one can only hope that they’ll

continue to release more of Melville’s films on DVD in the

future. Besides a beautifully restored print of the film,

the new DVD comes with some great extras including archival

interviews with Melville and actors Jean-Paul Belmondo and

Serge Reggiani, audio commentary by film scholar Ginette

Vincendeau, the original theatrical trailer and a thoughtful

new essay by film critic Glenn Kenny.

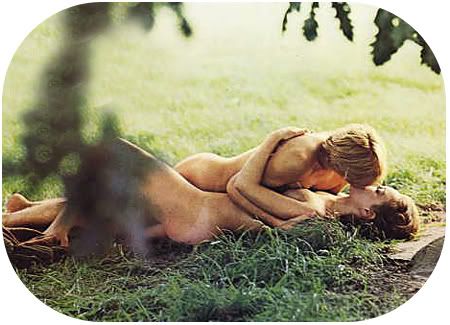

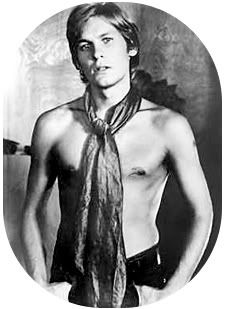

Helmut Berger in Ludwig (1972) 10. Ludwig(KOCH Lorber Films)

Few directors know how to create epic historical

dramas like Luchino Visconti and Ludwig (1972)

is one of the director’s most ambitious efforts.

This four hour film is not without its flaws,

but if you take the time to watch this dramatic

retelling of the life of the “mad” Kind Ludwig II

of Bavaria you’ll be rewarded with some lush cinematography,

grandiose set designs, fabulous period costumes and great

performances from the film’s impressive cast.

Like many of Visconti’s previous efforts, the film offers

viewers an intelligent critique of the powerful and wealthy,

while celebrating their extravagances and mourning the

passage of time. One of my favorite actors is the Austrian

born Helmut Berger who stars as King Ludwig here and this

film offered him one of his most expansive and fascinating

roles. Visconti and Berger were long-time lovers and they

work extremely well together. Visconti indulged Berger

during the making of Ludwig and gave the actor plenty of

freedom to bring the mad King to life, but he also knew

when to rein him in. The film also features Trevor

Howard as composer Richard Wagner, Silvano Mangano as

Wagner’s mistress Cosima Von Buelow and Romy Schneider

was smartly cast as the Empress Elisabeth of Austria.

The lovely and talented Romy Schneider had previously

become a star due to her sympathetic portrayal of the

young Empress Elisabeth in the popular Austrian Sisi films and

she brings a lot of experience and skill to her role.

This impressive two disc DVD set from KOCH Lorber Films

features a digitally restored and re-mastered widescreen

print of the film and it’s loaded with extras including a

documentary about director Luchino Visconti,

a profile of actress Silvano Mangano and an interview with

costume designer Piero Tosi. I wish one or two of the extras

included with the DVD focused a bit more on the film’s star

Helmut Berger, but that’s a minor complaint.

This release is a real treat for Luchino Visconti fans like myself. The second half of my Favorite DVDs of 2008 list can be found here.

by Cristina Neri | February 28, 2009

Yesterday was Elizabeth Taylor’s 77th birthday.

Last year I wasn’t able to properly complete my

tribute to Taylor and I never finished writing about

a few of her films that I want to cover here sooner or

later, but today I thought I’d offer up a few brief

thoughts about her 1973 film, Ash Wednesday.

The paper thin plot of Ash Wednesday was summed up

perfectly by Roger Ebert in his review of the film

(published in his book I Hated This Movie) so I’ll

just quote him here:

“Ash Wednesday is a soapy melodrama that isn’t much

good as a movie but may be interesting to some audiences

all the same. It’s about how a 50ish wife

(Elizabeth Taylor), her marriage threatened by a

younger woman, has a face-lift in order to keep her

husband (Henry Fonda). It doesn’t work, but she gets a

nice winter in a ski resort out of it and an affair

with Helmut Berger.”

In all honesty that’s all there is to Ash Wednesday.

Trying to read some kind of subtext into Jean-Claude

Tramont’s flimsy script is utterly pointless so I won’t

bother. But when you consider the film’s 1973 release date,

the movie becomes somewhat notable for the way it dared to

tackle aging and beauty myths. In a memorable opening

sequence featuring actual footage from real operations;

viewers are subjected to an appropriately ugly and

unflinching look at cosmetic surgery as an elderly

Elizabeth Taylor decides to reluctantly go under the knife.

The makeup used to age Taylor (who was only 41 years old)

is pretty convincing, but she’s soon magically transformed

into the flawless middle-aged beauty that she actually

was at the time.

As the film slowly unfolds the audience is supposed

to be surprised by the May-September romance that

blossoms between 41 year-old Elizabeth Taylor and

29 year-old Helmut Berger, but that’s impossible.

Taylor still looked stunning at 41, which only manages

to muddle the plot. And when a ragged looking Henry Fonda

finally shows up as the cold distracted husband who is

having an affair behind Taylor’s back you’re left

wondering, why? There is a great scene where Taylor

confronts Henry Fonda telling him that she only had

plastic surgery in an effort to get him back, but Fonda

isn’t moved. Elizabeth Taylor’s character is forced to

realize that plastic surgery can’t save a marriage that

is emotionally dead.

The only real reason to sit through Ash Wednesday is to

watch lovely Liz and handsome Helmut Berger exchange

passionate glances and loaded words until they finally

fall into bed together. Elizabeth Taylor looks amazing

in the film and waltzes through it wearing some fabulous

Edith Head costumes and impressive Valentino fashions.

Her performance is also rather convincing and low-key

even if the material is completely forgettable.

She could have easily hammed it up, but Taylor obviously

has some emotional connection to the character she’s

playing and her sincerity is believable. On the other hand,

the talented Helmut Berger is wasted here and he seems

more than a little distracted in the film.

Rumor has it that Taylor’s husband Richard Burton thought

Ash Wednesday was incredibly vulgar and he was bothered by

the love scenes Berger shared with Taylor.

Richard Burton was sure that Berger and Taylor were having

an affair off screen as well, even though Helmut Berger was

open about his homosexuality. According to writer

Dominick Dunne who produced Ash Wednesday,

the behind-the-scenes drama happening during the making of

the film was more interesting than anything going on in

front of the cameras. Elizabeth Taylor was chronically late

to the set prompting Paramount Studio head Robert Evans to

fly off the handle and the fights that occurred between

Taylor and Burton were explosive enough to frighten the rest

of the cast and crew.

Director Larry Peerce previously had some success directing

episodes of Batman (1966) and The Wild Wild West (1967),

as well as popular films such as Goodbye, Columbus (1969),

but he brings none of the style or humor from his earlier

efforts to Ash Wednesday. The film takes much too long to

get going and there aren’t enough bedroom scenes in it, but

what does occur is a bit steamy so if you happen to love

watching Elizabeth Taylor and Helmut Berger on screen as

much as I do, you might find Ash Wednesday worth a look.

On the other hand, Ash Wednesday is really just a blueprint

for the type of dull and lurid melodrama that you might find

playing on the Lifetime Movie Channel at 1am. And if I didn’t

know any better I’d swear the script was adapted from some

Harlequin romance novel. If that sort of thing holds no appeal

you should avoid this film at all cost.

Ash Wednesday is only available on video and I can’t really

make a case for its DVD release. Many of Elizabeth Taylor’s

adoring fans would probably like to see the film become more

easily available, but for now they’re going to have to pick up

a used copy of the Paramount VHS at Amazon if they want

to see it.

You can find more images from the film in my Ash Wednesday

Flickr Gallery.

RIP Ruslana Korshunova

Supermodel falls to her death

from Manhattan building

June 29, 2008

In what is being called “an apparent suicide,”

fashion model Ruslana Korshunova fell to her death from a building in Manhattan’s Financial District on Saturday.

Korshunova appeared in the European Vogue magazine as well

as ads for Marc Jacobs, DKNY, and Vera Wang. She was 20 years old.

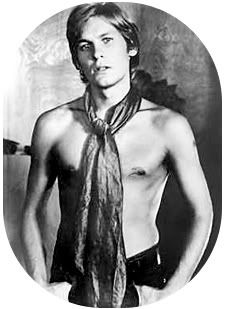

by Cristina Neri | April 8, 2007

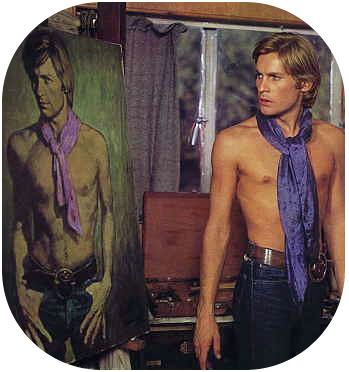

I recently watched Massimo Dallamano’s Dorian Gray for

the third or forth time and I was inspired to write about

the movie. When the opportunity to contribute to Neil’s

Trashy Movie Celebration Blog-a-thon arrived I figured a

review of the film would be the ideal contribution since

it definitely qualifies as a trashy movie - eurotrash to

be exact - and it’s also a personal favorite.

Oscar Wilde’s classic tale of a vain, wealthy and beautiful

youth who’s sins are preserved in a portrait that ages

horribly while he remains young, has been adapted for the

screen many times. But I don’t think any movie except Massimo

Dallamano’s 1970 film has been able to really capture the

decadence of Wilde’s original story. Dallamano set his film

version of Dorian Gray in the present, which at that time was

the height of the sexual revolution in the late sixties.

This gave the director ample opportunity to explore the world

of swingers, uninhibited sex and gender bending through the

eyes of the curious Dorian Gray.

The movie stars the attractive German actor Helmut Berger

who made a name for himself in some of Luchino Visconti’s

best films including The Damned, Ludwig and Conversation Piece,

but he also appeared in many European thrillers and various

other trashy movies such as the notorious Salon Kitty.

The critics have never been too kind to Berger, which is a

shame because when he’s good, he’s very very good and when

he’s bad, he’s still a lot of fun to watch. Helmut Berger

has what so many actors lack today,charisma and screen presence.

Massimo Dallamano couldn’t have picked a better actor to play

the vain and self absorbed Dorian Gray. Helmut Berger is

clearly enjoying himself in the role and it’s easy to believe

that women and men of all ages and sexual persuasions are

attracted to him. Berger’s erotic persona and fluid sexuality

are used to their fullest extent in Dorian Gray and the

audience is easily able to project their own fantasies into

the movie if they’re willing.

The film opens with a shot of Dorian’s blood-stained hands

signaling what’s to come and then we’re immediately taken to

a cabaret where a drag queen is performing as Dorian and his

companions watch. When the drag queen strips down to reveal

sexy black lingerie, you know you’re in for a wild ride.

It’s impossible to watch the opening moments of Dorian Gray

and not be reminded of Helmut Berger’s own drag performance

in Visconti’s The Damned where he impersonated Marlene Dietrich.

The Damned was released a year earlier and Dallamano’s sly

tribute to Helmut Berger’s earlier performance in Visconti’s

film acts as a wonderful introduction to Dorian Gray.

Dorian’s friend Basil Hallward is played by the veteran

British actor Richard Todd. Basil is the artist who paints

Dorian’s doomed portrait and Richard Todd is convincing as

Dorian’s concerned and more mature friend. Thanks to Basil,

Dorian is introduced to the much more conniving and depraved

Henry Wotton who’s brilliantly brought to life by another

veteran British actor, the great Herbert Lom. Henry and the

beautiful Alice (Maria Rohm) introduce Dorian to the underside

of high-society and encourage Dorian’s hedonistic lifestyle.

As the film progresses Dorian meets his first love interest

in the tragic figure of an aspiring Shakespearean actress

named Sybil Vane. Sybil is played by the pretty Swedish actress

Marie Liljedahl who’s mostly remembered for the erotic films

she made including Jess Franco’s Eugenie. In Dorian Gray we’re

asked to believe that Marie Liljedahl is an innocent virgin

seduced by the devilish Dorian and it actually works.

Thankfully Dallamono doesn’t bore us with their courtship.

Dorian and Sybil seem to fall in love at first sight and their

relationship quickly turns sexual. The audience knows they’re

in love because key lines from Shakespeare’s play Romeo & Juliet

are played over and over again in the background as the two lovers

gaze into each other’s eyes and roll around in bed together.

Sybil devotes herself to Dorian, but after he falls in love with

his own portrait, Dorian can really only be faithful to himself.

Under Henry’s influence Dorian seems to forget his feelings for

the naive Sybil and begins to dabble in the decadent lifestyle

that will soon destroy him.

At first Dorian’s passions are rather mild, and include occasional

make-out sessions with wealthy socialites, as well as fancy parties

with expensive foods and lots of booze. Sybil doesn’t appreciate

Dorian’s upper-class friends or approve of their lifestyle, and

her jealousy turns to delirium when she notices other women

flirting with Dorian.

After Sybil suddenly kills herself in an act of desperate passion,

Dorian succumbs to his most depraved desires. He claims that he

feels nothing after Sybil’s death, but Dorian seems to want to

bury his grief in random sexual encounters, yacht parties and

go-go clubs. He visits bath houses with Herbert Lom, cruises

the docks for sailors and seduces a wealthy elderly lady in a

horse barn. The Dorian in Massimo Dallamano’s movie has no

inhibitions and we get to enjoy his decadent adventures as

they’re exposed.

There’s an unusual voyeuristic element added to the film

after Dallamano introduces a pretty female photographer

into the story. The photographer starts following Dorian

around and snapping photographs of him whenever she can.

She seems to become Dorian’s constant companion and helps

him blackmail his friend Alan (Renato Romano) by snapping

photos of Alan’s lovely wife (Margaret Lee) and Dorian

together in bed.

As you may have noticed by now, many of the actors in

Dallamano’s film are regulars in Jess Franco’s movies.

I’ve read that Franco was originally supposed to direct

Dorian Gray before Massimo Dallamano took over so it’s not

surprising that the movie’s cast resembles the cast of

a Franco film. It would have been interesting to see what

Franco could have done with the story and the cast, but

Dallamano’s a skilled director, writer and cinematographer

and his talents are on full display in Dorian Gray

Dallamano’s film is fairly faithful to Wilde’s original

story and where previous film adaptations rarely suggested

any of the sexual decadence that Wilde could only hint at

in his book, Dallamano’s movie revels in it. Critics have

called the film trashy and lifeless. The movie is undoubtedly

trashy, but it’s anything but lifeless, especially when it’s

compared to other film adaptations of Oscar Wilde’s

original story

Oscar Wilde was part of the Aesthetic Movement in British

literature, which developed the “cult of beauty” and believed

that the arts should offer cultivated sensual pleasures instead

of morality and sentimentality. The British Aesthetic movement

stressed the importance of symbolism and suggestion rather than

statement. Intentional or not, Dallamano’s film follows an

aesthetic that would have made Wilde proud. The movie celebrates

the fashions, decadent lifestyles and sexual freedoms of

the times that it was made in with lots of style and very

little sentimentality. The beautiful Dorian and the sensual

pleasures he indulges in are captured with an unflinching eye

and no concern for morality.

Of course in some ways Wilde’s Dorian Gray was a statement

against everything the Aesthetic Movement stood for.

The story of Dorian Gray celebrates decadence just as it

criticizes its indulgences. As Dorian’s eventual end

approaches he is forced to pay for his sins, but the joy

of traveling with Dorian on his hedonistic journey is not

lost in Massimo Dallamano’s film as it is in so many other

movie adaptations.

One of the most interesting things Dallamano does with

Dorian is to wrap him in Zebra fur. Dorian has zebra drapes

on his windows and zebra fur rugs on his floors. By the end

of the film Dorian is dressed in a floor length zebra fur

coat that would make many pimps in 1970 envious.

Zebras each have a unique stripe pattern that is similar

to a persons fingerprint and a zebra often represents

individuality. In occult symbolism a zebra can even suggest

knowledge both seen and unseen, and their stripped patterns

of black on white or white on black can suggest that what

you see is not always what you get. When the zebra appears

in your dreams it can even indicate a time of change or

represent hidden knowledge that is about to be revealed.

I have no idea if the director had anything in mind when

he draped Dorian’s body and decorated his home in zebra fur,

but I think it’s fascinating to explore what this possible

symbolic gesture might suggest.

Finally, I can’t talk about Dallamano’s movie without

mentioning the exceptionally groovy score by composer

Giuseppe De Luca (A.K.A. Peppino De Luca).

It adds many layers to the film and it also celebrates

the movies most decadent moments with lots of rhythmic flair.

Unfortunately the film is only available on VHS at the moment

and the quality of the prints that are available are rather

awful. Hopefully a DVD company like Blue Underground or

Mondo Macabro will rescue Massimo Dallamano’s Dorian Gray

and restore it to it’s original splendor. The movie really

deserves another look and I think critics will be able to

appreciate its eurotrash charms now that over 35 years have

passed since it’s original release.

by Cristina Neri | March 22, 2007

David Zuzelo who runs the terrific blog Tomb it

May Concern started what he refers to as The Eurotrash

Pinnacle Project. It’s an effort to bring together a list

of favorite Eurotrash films from every genre imaginable

including eurohorror, giallo, eurospy and spaghetti westerns.

I recently contributed my own list of Top 10 Eurotrash films

with an additional 10 titles tacked on the end for good

measure, since selecting only 10 was an impossible task.

In my brief commentary for the first 10 films I listed,

I used the word “sexy” a lot, which isn’t too surprising

since sex often plays an important part in Eurotrash films

and some of my favorite actors (Klaus Kinski, Alain Delon,

Terence Stamp, Helmut Berger and John Phillip Law) often

show up looking very sexy in the movies I mentioned.

You can find my list of favorite Eurotrash films now posted

over at Tomb it May Concern. Be sure to click on the label

link “Eurotrash Film Pinnacle Project” at the bottom of the

entry because it will take you to the the rest of the great

movie lists contributed by others.

|